An online thinkspace, where progressive philosophers and practitioners from across the globe can connect through community and inquiry to carry out the movement’s important commitment to the intersection of democracy and education.

Read our most recent postS

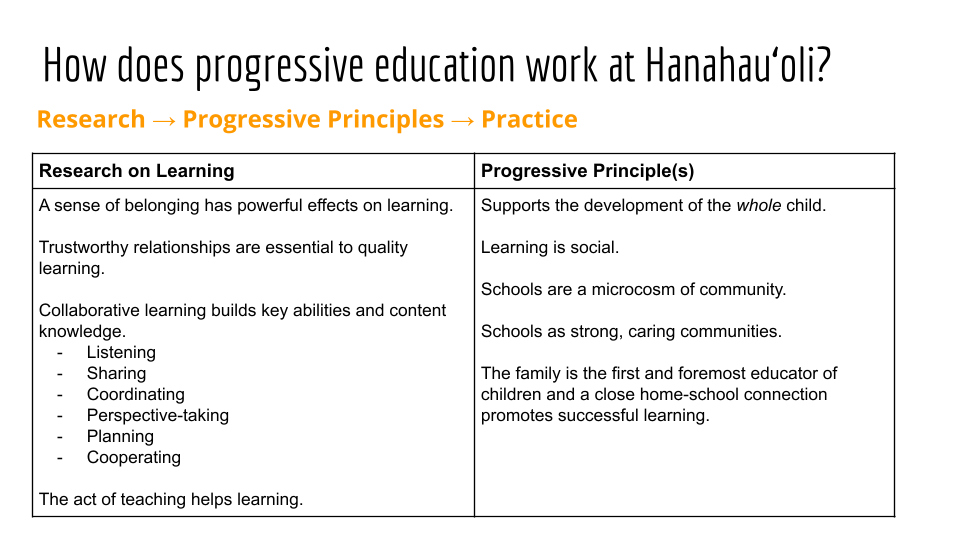

A number of our authors have written about a progressive education approach to curriculum design over the years, but surprisingly, it is hard to find progressive education writers that focus on lesson planning. For example, in this post I give a brief introduction to the history of progressive education curriculum design, then highlight Hanahau‘oli School’s approach to developing “integrated, interdisciplinary, and thematic” units of study. In Gabby Holt’s blog about concept-based learning, she emphasizes unit planning and the ways progressive education units based on concepts rather than topics can cultivate and build students’ enduring understandings over time. Other bloggers, like Brett Peterson who published this incredible read, “Uncovering The Progressive Past: The Origins of PBL,” underscores the progressive education movement’s role in introducing educators “to a curriculum inspired by and designed with the project,” also known as project-based learning (PBL). In each of these pieces, it is clear that the progressive education tradition favors longer-term units of study or projects as the foundation for curriculum design, rather than shorter lessons or discrete lesson planning.

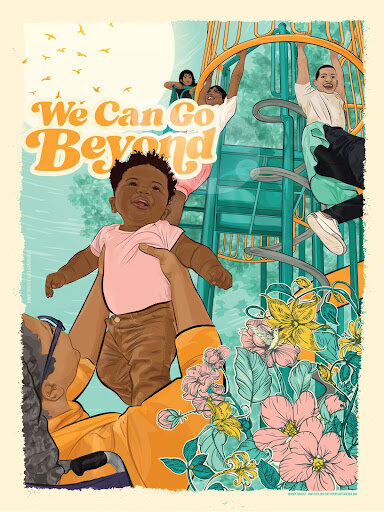

In August 2025, Hanahau‘oli School shared a refreshed Mission Statement and a thoughtfully articulated framework of Guiding Beliefs—the result of a reflective and collaborative process involving voices from across the school community. While grounded in the values, philosophy, and traditions that have guided Hanahau‘oli since 1918, this renewed mission looks ahead with hope and intention. It embraces the changing world children live in today—and the one they will help to create—with a spirit of joyful wonder and purpose.

Browse previous posts

by topics in progressive education

Progressive education Philosophy

Progressive Education Curriculum

Progressive education Teacher professional development

Connecting progressive education history to today

Progressive Education Pedagogy & Practice

Progressive Education Assessment

Progressive Educator Reflections

Social Justice Education

Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy: A Blog for Progressive Educators is edited by Amber Strong Makaiau and Veronica Kimi. To support the ongoing professional development of educators seeking to share their ideas and success stories via the blog, Makaiau and Kimi provide 1:1 conferencing and writing support during the publication process. Click here to learn more about contributing to the blog.

We are Federica Gallone and Federica Lentini – two educators who feel most alive when we are learning with children. Our professional lives have unfolded in early childhood settings, where relationships, curiosity, and wonder shape our days. We have worked closely with children as teachers, atelierista, and pedagogista, accompanying students’ thinking through materials, dialogue, light, and documentation. Our classrooms and studios are spaces of research—places where questions remain open and children’s ideas are made visible, respected, and revisited.