By Amber Strong Makaiau

Abandon the notion of subject-matter as something fixed and ready-made in itself, outside the child’s experience; cease thinking of the child’s experience as also something hard and fast; see it as something fluent, embryonic, vital; and we realize that the child and the curriculum are simply two limits which define a single process (1902, p. 189).

―from John Dewey’s The Child and the Curriculum

Progressive education is a living work in progress, a continually changing “mode of associated living” (Dewey, 1916, p. 87) that must be reflected on, evaluated, and sometimes modified to keep up with–and more importantly stay ahead of–the times to achieve its mission of creating “a better future society” (p. 20). Curriculum, within the context of a progressive education, is no different. The subjects, concepts, tasks, planned activities, desired learning outcomes and experiences, and the general agenda to reform society–all of which Schubert (1987) describes as defining characteristics of a progressive education curriculum–must be studied and improved upon over time. Katherine Camp Mayhew and Anna Camp Edwards (1965) said it best when explaining how the pioneering progressive education curriculum was created at John Dewey’s Laboratory School at the University of Chicago: “ideas [in education, schooling, and curriculum], even as ideas, are incomplete and tentative until they are employed in application to objects in action and are thus developed, corrected, and tested” (p. 3). Created using a design and implementation process described in my opening quote from John Dewey–curriculum is somewhat meaningless, until it is experienced by students, reflected on, and made better by members of a school community.

This has been the approach to curriculum development and practice at Hanahau‘oli School over the past century. Grounded in an enduring philosophical throughline and many long-standing curricular traditions that have lasted from the school’s founding to today–the overall professional culture and method for designing curriculum at Hanahau‘oli is characterized by a spirit of continuous improvement, the strong desire to build on the school’s strengths, and the necessity of “respond[ing] to, and plan[ing] for, changing times” (Peters, 2019, p. 56). In this blog, I document the evolution of Hanahau‘oli School’s progressive education curriculum and explain how the curriculum of today–specifically the integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study–has benefited from steadfast philosophical roots and a commitment to iteration and development over time.

Progressive Education Curriculum at the Turn of the 20th Century

At the onset of the American progressive education movement there were many influential texts that clearly and distinctly articulated the key characteristics of a progressive education philosophy and theory (see my previous blog on The Progressive Education Spectrum). While this strong conceptual foundation was instrumental in launching the number of progressive schools that were being established at the turn of the 20th century (including Hanahau‘oli), the task of translating progressive education curriculum theory (see Dewey’s The Child and The Curriculum) into practice was more challenging. Mayhew and Edwards (1965) give these insights from the curriculum design process at the University of Chicago Dewey School (1896-1903):

The task that lay before those who worked out the educational implications of these newly formed theories was a difficult one. It was difficult because it necessitated the discarding of many established methods of teaching and learning. It meant careful study of the story of education, especially of those periods and types of civilization when there was no rift between experience and knowledge, when information about things and ways of doing grew out of social situations and represented answers to social needs, when the education of the immature member of a society proceeded almost wholly through participation in the social or community life of which he was a member, and each individual, no matter how young, did certain things in the way of work and play along with others, and learned, thereby to adjust himself to his surroundings, to adapt himself to social relationships, and to get control of his own special powers…‘He must learn by experience’ is an old adage too little heeded by modern methods of schooling. Too often these methods take for granted that there is a shortcut to learning, and that knowledge apart from its use has meaning for the developing mind. The memorizing of such knowledge has come to be a large part of present-day education, with the result that great masses of young lives have been denied the thrill of experimental living, of finding the way for themselves, of discovery, of invention, of creation (1965, p. 21).

The overarching question at the time: What exactly might a progressive education school curriculum grounded in student-centered experience, discovery, invention, and creation look like?

The founders of Hanahau‘oli School and the initial cohort of faculty and staff explored this question wholeheartedly. In 1919, the school published a bulletin stating, “Our aim is to give the child opportunities for self-expression and to provide, through the interests and activities of the school, occupations necessary for the development and unfolding at each stage of his individual powers and capabilities; to show him how he can exercise these powers, both mechanically and socially, in the little world he finds about him” (Palmer, 1968, pp.15-16). To accomplish these aims the faculty and staff developed, tested, reflected on, and made improvements to the earliest iterations of the Hanahau‘oli School curriculum. As a result of this process, the curriculum became more “established” and was eventually documented in Louisa F. Palmer’s Memories of Hanahau‘oli: The First Fifty Years. In this publication, Hanahau‘oli School’s progressive education curriculum is recorded as including: social studies (Hawaiian history and culture, world civilizations, medieval history, American history, Egypt, Greece, China, and other world geographies and cultures) as an anchoring “subject” for integrating reading, writing, math, and science; shop and art as integrated hands-on humanities and science experiences; music; creative dramatics; school traditions (e.g. the celebration and study of Makahiki, holiday programs, and the creation of stepping stones); and ample opportunities to engage in cooperative learning as a method for experiencing ideal democratic citizenship first hand (Palmer, 1968). In summary, Palmer (1968) explains, “the briefest and best expressions of Hanahau‘oli philosophy have been learning by doing, which includes the creative aspect, and learning from real and first-hand experience whenever possible” (p.17).

Over the years–in an effort to improve upon the experiences of students, respond to the changing world, and get closer to a proven method for effectively translating progressive education curriculum theory into practice–subsequent generations of Hanahau‘oli faculty and staff built off of the school’s seminal curriculum by continuing to develop, test, reflect upon, and refine it. While some of Hanahau‘oli School’s earliest curricular experiences, established at the school’s founding, are still carried out today (e.g. stepping stones, Makahiki, morning flag, Friday assemblies, and the in-depth study of Greek culture, government, sport, and mythology), other aspects of the curriculum have changed. A particularly noteworthy turning point in the overall advancement of Hanahau‘oi’s curriculum came about in the 1980’s, 1990’s, and early 2000’s. This was the adoption of a “conceptual approach” to integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic unit design and it was initiated by Robert G. Peters, Hanahau’oli’s tenth Head of School.

Concept-Based Curriculum Design and Integrated, Interdisciplinary, Thematic Units of Study

Based on the scholarship of Hilda Taba (1966), concept-based curriculum centers concepts as the “foundational organizers for both integrated curriculum and for single subject curriculum design” because they “serve as a bridge between topics and generalizations” (Erickson, 2001, p. 23). Taba, “a visionary educator of the 1950’s and 1960’s, saw the value of conceptual organizers for content” (p. 23) and laid the foundation for more modern approaches to the curriculum design process, which call on educators to start with what they know about students’ before they formulate objectives and select content. Aimed at increasing the “intellectual functioning of students” (p. 23), Taba also proposed that “content coverage could be focused and delimited by letting the main ideas–the generalizations–determine the direction and depth of instruction. She held that specific content should be sampled rather than covered” (Erickson, 2001, p. 24). Peters encountered other progressive schools adopting Taba’s approach to curriculum design and used her research, along with the influential writings of George J. Posner (1995) to launch major curricular revisions at Hanahau’oli at the end of the 20th century. This included the introduction of concept-based integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study in the mid to late 1980’s with ongoing revisions to curricular units and topics into the 1990’s.

The integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic and conceptual approach to curriculum design and instruction is now a hallmark of progressive philosophy and pedagogy. Philosophically, it is a “naturalistic pedagogy (which arises from the needs, interests and capacities of the child and responds to the will of the child) and a skill-based curriculum (which focuses on providing the child with the learning skills that can be used to acquire whatever knowledge he or she desires)” (Labaree, 2005, p. 280 - 281). In practice, “interdisciplinary studies, thematic units and the project method” (p. 281) address the traditional American school system’s continued “lower-level love affair with trivia” (Erickson, 2001, p. 20). Advocated for by scholars like Lynn Erickson in the early 2000’s, this approach to curriculum design and implementation is now grounded in years of studying how children learn best. Erickson’s (2001) original research concluded, “when students are encouraged to think beyond the facts and connect factual knowledge to ideas of conceptual significance, they find relevance and personal meaning. When students become personally and intellectually engaged, they are motivated to learn because their emotions are involved. They become mind-active rather than mind-passive” (p.20). The introduction of the concept-based approach to designing integrated, interdisciplinary thematic units of study was a perfect match for Hanahau‘oli School, both philosophically and practically.

And at the same time that this approach to progressive education curriculum design was being developed, tested, and reflected on at Hanahau‘oli, Peters and the school community were also studying ways to better organize teaching and learning groups at the school. Driven by the desire to more closely align the school’s organizational structures with its progressive education philosophy and beliefs, faculty and staff were exploring the benefits of team teaching and multiage classrooms (Peters, 2019). Finally, in 2000, Hanahau‘oli made the move and reorganized the school so that teachers could all work in teams and students could learn in a multiage educational environment. At this critical point in the Hanahau‘oli’s history, faculty and staff (with input from the board, families, and children) dedicated themselves to further developing, testing, and refining the school’s integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study.

About this moment in the school’s history, Peters (2019) writes:

The change [to team teaching and multiage classrooms]…raised questions related to unit design and assessment. Initially there were a few ‘curricular collisions’ caused by duplication of unit topics, requiring a re-examination of age-level conceptual themes and topics of study. Each of the multi-age classrooms defined a two-year cycle of thematic units that supported the development of a global concept, such as interdependence or survival/adaptation, which spiraled through the curriculum helping children to build upon and expand their understandings. How to report children’s progress over time became a central issue as faculty sought to demonstrate growth…Children’s skill development in language arts and math would be reported on a continuum corresponding to overlapping age levels (three to five, five to seven, etc.) with descriptors to show what a child could do…And teachers developed their own continua of understanding for thematic units related to the major concepts supported by their units once again showing what a child understood rather than in relationship to a static body of information (p. 57 - 58).

It was this transition that catalyzed the need for established units of study at each multiage grade level cluster (JK, K/1, 2/3, 4/5, and 6), which could be taught over a two-year cycle.

Today, the curriculum at Hanahau‘oli School continues to be designed using two-year cycles of integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study that are centered around concepts that spiral or progress throughout the students' eight-year journey at the school, increasing in complexity from JK to 6th Grade. The concepts are derived from disciplines in the sciences and social studies. They are selected to support children as they explore three main questions throughout their eight-year journey at Hanahau‘oli School: Who am I? How does the world work? And Where and how do I fit in that world? Factual information is valued as a foundation for concept development, but it is not the focus for assessing learning. The more traditional academic skills are taught in an integrated fashion when appropriate to lend meaning and relevance, discreetly when needed, for mastery. National curriculum standards from each discipline help to define the essential concepts, processes, and skills infused throughout the curriculum.

While units and themes are repeated every two years (within each multiage grouping of K/1, 2/3, 4/5); each time the units are taught, teachers take into account the unique group of students and families that make up their classes that year as well as the changing world. As a result, parents, community, and society at-large are a part of the curriculum at Hanahau‘oli School, and unique “real world” experiences (e.g. learning trips, guest teachers, experiments, spontaneous teachable moments, and informed action projects on campus and beyond) are integrated into the units each year. The units are also taught with the support of specialist teachers who design learning experiences that integrate reading, writing, math, art, music, shop, physical education, library, Hawaiian language and culture, and Mandarin into the units. Specialists collaborate with teachers to design learning experiences that will best fit the unit during that school year. It is also important to note, since implementing thematic units, faculty and staff have recognized the need to map out a progressive JK-6 Language Arts and Math curriculum that can be integrated into the units as well. This curriculum was developed and is continually studied by curriculum committees, which are composed of teachers representing each grade level cluster (JK, K/1, 2/3, 4/5, and 6).

With the acknowledgment that progressive education curriculum is never set in stone, in the 2022-23 school year, Hanahau‘oli School faculty and staff worked with the Director of Curriculum & Innovative Technology to begin the process of electronically documenting all of the school’s thematic units of study. This documentation process is aimed at supporting new faculty, and better communicating curriculum with families and visitors. As a result of this process, teachers are now posting a “curriculum summary” of the thematic unit currently being taught on a board outside their classroom. This posting includes a QR code so that families and visitors can learn more about the curriculum when they come to observe and participate in school activities.

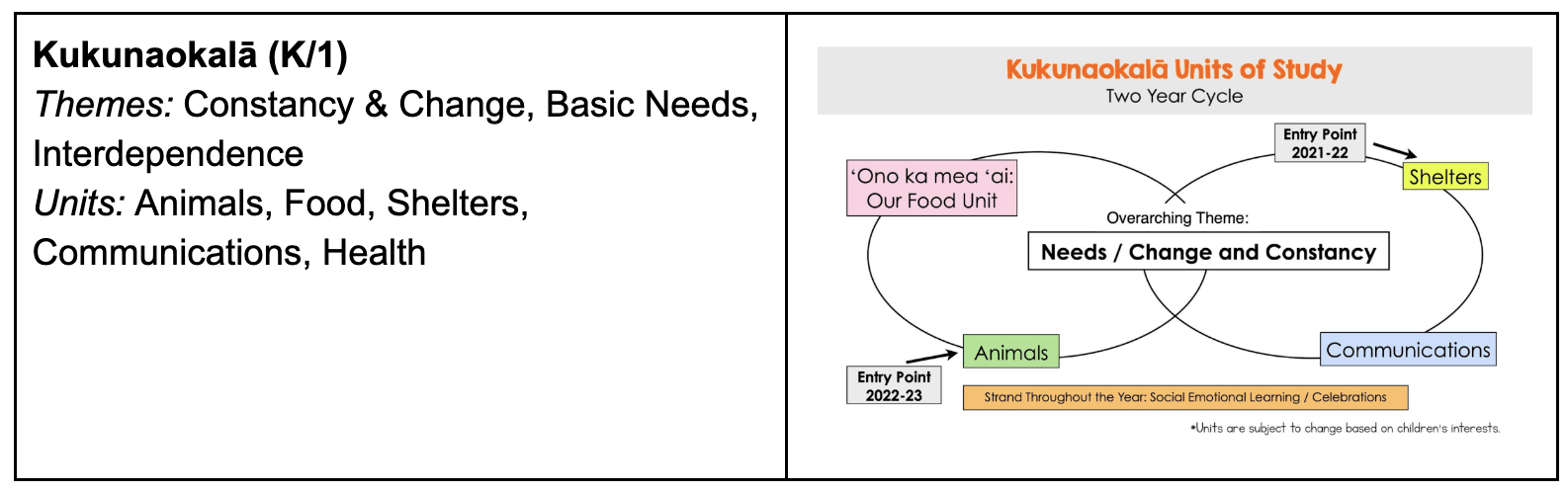

Also, to illustrate “the big picture,” regarding the two-year cycle of thematic units being taught in each grade level cluster (JK, K/1, 2/3, 4/5, and 6), the tables below were developed by each of the current teaching teams at Hanahau’oli School.

While these descriptions and graphics are representative of the most up-to-date integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study–the Hanahau‘oli School community continually works to modify units in response to our students, new research, and the changing world.

Progressive Education Curriculum of Tomorrow

As progressive educators at Hanahau‘oli continue to study children and society, there are a number of key elements they are currently taking into consideration as they design, experiment with, and improve upon the school’s integrated, interdisciplinary, thematic units of study. One area of interest is finding ways to explicitly integrate key social justice education concepts into the units. The Social Justice Standards from Learning for Justice have been a valuable resource for grounding this work. Based on Louise Derman-Sparks’ four goals for anti-bias education in early childhood, the standards “provide a common language and organizational structure educators can use to guide curriculum development and make schools more just and equitable” (Learning for Justice, 2023). At Hanahau‘oli School, faculty and staff are using the four domains– identity, diversity, justice, and action–and their accompanying standards to revise and update units so students have opportunities to explore these concepts throughout Hanahau‘oli School’s eight-year spiraling curriculum. As a result, many of the units are being redesigned so students have the opportunity to “take informed action” (as it is described in the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework) at the school or in the community at-large at the culmination of each unit. In light of the tremendous work we all have to do to address climate change, many of the informed action projects engage students in environmental and sustainability work. All of these changes, while they are grounded in our contemporary world, help move the school closer to achieving the century-old democratic aims of the progressive education movement (Dewey, 1916).

Also, in the spirit of being better “teacher scientists,” Hanahau‘oli faculty have also done a lot of work in recent years to study the latest scholarship and research regarding strategies for teaching mathematics, literacy, and language arts. This has included visiting more than 20 different progressive schools during the 2019-2020 school year to bring back new ideas for integrating math, literacy, and language arts across the eight-year curriculum and within the thematic units. This was the school’s Hele A‘o initiative, which has led to a pilot of the Math Investigations 3 curriculum (observed in numerous progressive schools) in our K-5th grades.

Finally, in addition to strengthening the social justice, informed action, and climate-conscious components of the thematic units of study, and bolstering the integrated math and language arts curriculum with the most up-to-date research, the school is also working on ways to “structure” more choice time and open-ended exploration and discovery into the school schedule and calendar. One example is the introduction of ‘Imi ‘Ike or enrichment week during the 2022-23 school year. Documented in Mike Travis’s May 2023 blog, this pilot was built off of past experiments at Hanahau‘oli in the 1980’s, 1990’s and during the school’s centennial in 2018. The faculty and staff of today, much like their predecessors, are committed to finding the best way to structure more free choice and exploration time into the school’s curriculum.

These are just a few of the ways the current generation of faculty and staff at Hanahau‘oli school are continuing to “develop, correct, and test” (Mayhew and Edwards, 1965, p. 3) methods for designing and implementing a progressive education school curriculum that honors Dewey’s 1902 philosophy presented in The Child and Curriculum. By “abandon[ing] the notion of subject-matter as something fixed and ready-made in itself, outside the child’s experience” curriculum design and implementation becomes a “process” (p. 189) rather than an outcome. Just like the progressive education movement itself, the project of democracy, and the ever-present need for creating a better future society–this is an ongoing process full of purpose, which makes the work of educators meaningful and important. I look forward to seeing what the next iteration of curriculum design and practice will look like at Hanahau‘oli School and other progressive education schools dedicated to the work ahead.

Works Cited:

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. The Free Press.

Erickson, H.L. (2001). “Concept Based Curriculum.” In Stirring the head, heart, and soul: Redefining curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press Inc. [pp. 33-36].

Labaree, D. (2005). Progressivism, schools and schools of education: An American romance. Paedagogica Historica, Vol. 41(1&2), pp. 275–288.

Mayhew, K. C. & Edwards, A. C. (2007). The Dewey school: The laboratory school of the university of chicago 1896 - 1903. AldineTransaction.

Palmer, L. F. (1968) Memories of Hanahau’oli: The first fifty years. Honolulu: Unknown.

Peters, R. G. (2019). Hanahau‘oli school: 100 years of progressive education. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing.

Posner, G. J. (1995). Analyzing the curriculum. McGraw-Hill.

Schubert, William H. (1987) "Educationally Recovering Dewey in Curriculum," Education and Culture: Vol. 07 : Iss. 1, Article 2.

Taba, H. (1966). Teaching strategies and cognitive functioning in elementary school children. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco State College.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Amber Strong Makaiau is a Specialist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Director of Curriculum and Research at the Uehiro Academy for Philosophy and Ethics in Education, Director of the Hanahau‘oli School Professional Development Center, and Co-Director of the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy MEd Interdisciplinary Education, Curriculum Studies program. A former Hawai‘i State Department of Education high school social studies teacher, her work in education is focused around promoting a more just and equitable democracy for today’s children. Dr. Makaiau lives in Honolulu where she enjoys spending time in the ocean with her husband and two children.