By Kristin Baker

In the first post of this two-part blog series exploring the relationship between “teachers as researchers” and progressive education, I defined teacher research, explained how it is critical to the profession, and told the story of how I stepped into the Teacher Scholar role at Hanahau‘oli School. I also introduced an example of a problem within my teaching practice that I named, researched, and sought solutions for through a series of teaching experiments during my semester as a Teacher Scholar at Hanahau‘oli School. In this second blog, I further illustrate the teacher scholar inquiry process I employed and share the strategies I tested to address my teaching problem. I also reflect on what I learned from my teaching experiment, and share how this learning will impact my teaching practice moving forward. At the end of the blog I advocate for the critical role that Teacher Scholars can play in K-12 schools.

Naming a Teaching Problem and Setting My Intentions

In the previous blog I shared how I honed in on the following problem of practice while teaching handwriting (or letter formation) within my early elementary classroom: The handwriting program I was providing was not very effective for teaching letter formation to the children who needed it most. I noticed this problem most when children were engaged in independent practice, using worksheets and workbooks that were intended to reinforce skills and habits that I had taught through a variety of other letter formation activities in my classroom (see Part 1 of this blog series). This was a problem I had seen before, within my first grade classroom at a different independent progressive school. However, during my semester teaching in a K-1 classroom at Hanahau‘oli School, I honed in on these specific observations:

The young learners who needed the most support with letter formation were returning to and reinforcing their old, not-so-efficient habits when working independently on handwriting worksheets, rather than transferring over the more efficient habits I was trying to teach them.

Those who were successful with independent handwriting practice were learners who had been naturally picking up efficient handwriting habits on their own and likely didn’t need this explicit practice in the first place.

To put it bluntly, I was wasting some children’s time and not meeting the handwriting needs of others through the activities in my classroom.

As a teacher-researcher, this critical lens is essential; only through humility and being honest about the complexity of my role can I continue to improve my teaching practice and better serve the learners in my classroom. Earlier in my teaching career, I would have hesitated to make such a statement under the false assumption that I, as teacher, am directly responsible for all of my students’ learning; but the reality is, children are learning all the time, both inside the classroom and out in the bigger world. With experience, I have come to know that sometimes learning needs are best addressed through direct, explicit instruction, and some of the deepest learning happens when a teacher gets out of the way, observes carefully, and provides guidance and support when needed. It is a teacher’s responsibility to be tuned in with students’ strengths and needs as learners to provide them with the style of guidance they need during each moment, and I hadn’t quite figured out what that looked like when it came to handwriting.

I was also noticing a disconnect between the more progressive, exploratory activities I was using to model and provide guided practice with correct letter formation and the more traditional pencil-paper handwriting practice I was offering my young students to practice these skills. I wanted to look holistically at the collection of handwriting instructions and activities I was providing for the young children in my classroom and develop a way to more smoothly bridge: modeling (“I do”), guided instruction (“We do”), and independent practice (“You do”). I wanted to create a more constructivist approach to teaching letter formation, giving children like Aly (who I introduced in the first post of this blog series) a more active and creative role in exploring and discovering patterns, grounding her in the consistencies when it comes to forming letters, as opposed to a more traditional approach that presents handwriting as a series of 52 different characters, each to be learned step-by-step from A to Z. I also wanted to leverage the curiosity and creativity of the young learners in my classroom around letter formation. I wanted to guide them through activities that would spark interest and engage senses, stimulate connections between letter shapes and names, build control and muscle memory using stroke sequences that are smooth and efficient, and result in clear and legible writing.

Narrowing in on the Questions to Guide My Inquiry

The inquiry process starts with careful observation, naming a problem, and setting a solution-oriented goal, then grows into a series of questions that will intentionally lead toward that goal. Here is the overarching question that I narrowed in on to guide my inquiry: How can I teach handwriting with a constructivist approach that includes exploration, discovery, art, and play?

As I began to explore this question, I recognized for the first time that handwriting instruction presents an opportunity to be deliberate in applying a progressive philosophy of teaching. The idea of constructivism is foremost to a progressive philosophy and pedagogy: it is the belief that the learner is central in an active process of building understanding. In my 19 years of teaching, I have witnessed the power of constructivism over and over; learners learn most deeply and can apply their learning to higher cognitive tasks when they build understanding through experience and discovery. It’s a joyful and mind-blowing kind of learning filled with “aha!”s and the intrinsic motivation to ask more and deeper questions on the quest for figuring out how everything works. And yes, there are times and circumstances when a more traditional “knowledge transfer” from teacher to student makes sense; up until this point, I had assumed handwriting was one of those areas of learning where you simply show the child how to do it. Then, over the course of this year as a Teacher Scholar at Hanahau‘oli School, I began to think: Almost everything else I do in the classroom feeds a sense of wonder and curiosity. Why can’t handwriting take a similar approach? Together, my students and I could build understanding about the architecture of the alphabet and strengthen the pathways between our brains and those tiny muscles in our hands that we use for writing.

In addition to my main research question, I also asked:

How can I create a series of questions that spark children to explore and discover the many similarities between letter shapes and use these similarities as a jumping off point for correct letter formation? This question is an offshoot of my main one and represents an intersection of the teacher and student inquiry processes. It is a line of inquiry to support and strengthen my teaching practice and simultaneously it is a line of inquiry around letter formation that will engage my students in a process of exploration and discovery.

How can I take a handwriting program I already know and have used and adapt it to my setting? I didn’t want to completely reinvent the wheel. This question is the next step in an ongoing process of developing an approach to teaching handwriting that works for the students in my classroom and it applies a pedagogy that is consistent with the progressive philosophy I share with Hanahau‘oli School. It also connects to a foundation of my line of inquiry, which comes from my experience with Handwriting Without Tears, which I will describe in more detail in the next section.

How can I leverage the home-school connection to better support children who need more guidance and consistency when it comes to learning to write letters? As a Teacher Scholar, I was engaged in a series of projects throughout the semester which included planning a Family Literacy Workshop to help parents and caregivers of young children understand how to best support their children’s reading, writing, and language development. I hoped that my “Handwriting Experiment” would help me develop replicable activities and simple, consistent language to guide letter formation that I would then share with families so they could provide familiar and consistent guidance at home.

Exploring Existing Research and Handwriting Programs

Questions are like dominoes, one leading to another in the inquiry process. If teacher researchers pay attention to their questions closely, they begin to see that there are many avenues for developing possible answers to the questions. Some answers emerge during the practice of teaching (e.g. by experimenting with a new approach to teaching handwriting with students). Other answers are found by consulting with existing scholarship, research and curriculum programs. In the case of my particular handwriting experiment, one particular question that rose to the surface and that required a deep dive into previous scholarship and research was: When are children developmentally ready for handwriting instruction?

My semester in a K-1 classroom at Hanahau‘oli School was the first time I had ever worked with 5 year olds and only my second experience working in a multiage classroom setting. As a new teacher at Hanahau‘oli School, I was participating in conversations between the Junior Kindergarten (4 year old) and K-1 teaching teams that brought into question what skills we expect children to learn at which grade levels, while also holding true to our understanding about the fluid nature of child development. I know that I am not the first person to ask and investigate questions like this and so I turned to the research of others.

Chip Wood incorporates the research from multiple generations of educational and child development researchers with his own research to remind us of these critical understandings around child development:

Stages of growth and development follow a reasonable, predictable pattern.

Children and adolescents do not proceed through each stage at the same pace.

Children and adolescents progress through the various aspects of development at their own rate.

Growth is uneven (Wood, 2017, p.7-8).

Just because one four-year old knows how to write the alphabet doesn’t mean we should expect all four-year olds to do so. As parents and educators, we need to trust that children will grow and allow them the time to do so; this doesn’t mean we are detached from the process, but we also don’t need to control and force children’s growth and learning into unrealistic timelines.

I consulted Wood’s (2017) Yardsticks: Child and Adolescent Development Ages 4-14 to help shape my expectations for the young learners in my classroom around handwriting. This is what I found in terms of physical development that seemed relevant to teaching handwriting:

Typical growth patterns of 4-year-olds:

Visual focus is on faraway objects;

Have trouble with close visual activities;

Fine motor skills not well developed;

Learn more though large muscle activity and constructive play than through desktop paper-and-pencil activities;

Mainly scribble writing and drawing;

Typically grasp pencil in whole fist and use arm, hand, and fingers as a single unit (p.35).

Typical growth patterns of 5-year-olds:

Reverse letters and numbers;

Find it hard to space letters, numbers, and words;

Still awkward with writing, handicrafts, and tasks requiring small movements;

Hold pencil with 3-fingered, pincer-like grasp; may need pencil grip to help them relax;

Ready to begin learning manuscript printing; not always able to stay within lines;

Tendency to write only uppercase letters (pp. 47-8, 52).

Typical growth patterns of 6-year-olds:

More aware of fingers as tools;

Fingers are sometimes clumsy and tasks need slowing down or repeated practice to achieve desired results;

Proper grasp of pencil;

Letters the same size or slightly larger than at five;

Spontaneous mixing of uppercase and lowercase letters;

Unpredictable spacing (pp. 60, 65).

Some 4, 5, and 6 year olds’ tiny hand muscles are developed to the point that picking up a writing tool and manipulating it with enough precision to scratch out the A, B, C’s is relatively easy. Others are still waiting for their hand muscles to develop, making the task of holding a pencil for a few minutes quite taxing when the pencil won’t behave as the child wants it to. This becomes emotionally taxing as well when the child is watching another child write with ease. As a progressive educator, I respect this. I believe that learning can and should be relevant (and interesting) to the learner’s life, and that the timelines adults have mapped out for the myriad of physical, academic, social, and emotional skills children are expected to “master” from kindergarten through 12th grade are far too narrow and anxiety-producing than they actually need to be. This is why individual growth is my primary measure of learning progress, not comparing children to their peers.

I also came across this image and a conversation among educators and occupational therapists in the U.K. that felt relevant to my teacher research. Dr. Hellion blogged about some insight from Ruth Swailles, a school improvement advisor:

(Hellion, 2019)

…Ruth commented: ‘An x-ray of a developed hand (around the age of 7) compared to an EYFS [Early Years Foundation Stage] age child’s hand is pretty informative.’ As an image, she believes it prompts us to think about handwriting and handwriting development occurring ‘in an age-appropriate way, matched to children’s physical development…It’s worth noting that it’s not just the size of the child’s hand which changes. The younger child has cartilage which will eventually become bone through the process of endocrine ossification. This occurs around the ages of 6-8yrs…The physiology of young children’s hands needs to be taken into consideration”. Ruth points out hand maturation takes many years longer than assumed and that overall dexterity takes time. Handwriting practice starts AFTER the foundations have been thoroughly laid (Hellion, 2019)

This information helped get me grounded in my expectations of 5-year-old students like Aly.

As I shared in the first blog, Aly is a kindergartener who gives writing a try in her journal and goes with the flow of other activities we do in the classroom. She is at a stage of development where writing is still on the outer periphery when it comes to relevance in her actual life; some 5 year olds are pretty intrigued by writing, others simply are not–yet. Like other five year olds, Aly can get along just fine in day-to-day life without writing. In fact, there are about 10 other things she could probably name in a heartbeat that are ahead of writing if Aly were to define her own learning priorities. This is why I wanted to make Aly’s interest in various art media and a spirit of creativity and exploration central to my teaching experiment. To stay true to my progressive philosophy and pedagogy, I wanted to teach Aly (and others) handwriting in accordance with their social, emotional, and physical development.

Experimenting with New Strategies

To build on what I was learning from previous scholarship and research and what I knew of Aly, I began planning a series of Handwriting Workshops that would take place over the course of 2-weeks everyday afterschool for 20-30 minutes with small groups of 2-3 children. While Aly was the inspiration, I also designed more broadly, knowing there are plenty of others in her cohort at a similar place in their development. I wanted to leverage Aly and other’s interest in working with various art media to fuel and grow her newly expressed interest in handwriting and support her and others at a similar stage of writing development to build skills that would help her participate successfully in the various writing activities that were part of her school days.

I have found that much of teaching in an early elementary classroom requires going back to basics, adopting a “beginners mindset” where I try to erase much of what I take for granted as second-nature skills and understandings. In my blank notebook, I started to re-teach myself how to form my letters, dissecting the process in order to find some building blocks that I might not have been aware of before. I began with a concept from the Handwriting Without Tears program: every letter in the alphabet, uppercase and lowercase, can be formed using a combination of two simple shapes–line and curve–in two different sizes, big and small.

I would open my blank notebook, uncap a marker, and start to play around with lines and curves, toggling between my dominant and non-dominant hand. I questioned (again) whether the habits I had determined “most efficient” for myself as a right-handed person are equally applicable to a leftie. I thought about muscle memory and fluency–the journey from deliberate, slow, labored movement to automatic, don’t-even-think-about-it fluency–as I wrote my letters. I discovered connections, patterns, new ways of thinking about something I’ve been doing over and over since I was a young child.

I started to think about the alphabet in terms of the first stroke of each letter. A starts with a big line, B starts with a big line, C starts (and ends) with a big curve. D–big line. E–big line. F–big line. G–big curve. Later I did the same with lowercase: a–little curve, b–big line, c–little curve, and so on. I started to think about framing this activity as an investigation: How many letters start with a curve? How many start with a line? I imagined children showing a few examples, doing a few together, then sending them off to work together to sort the uppercase letters, then later the lowercase letters, into two categories: “starts with a line” and “starts with a curve.” We all would come back and hash out the results of our investigation, talk about why we agree or disagree with our sorting decisions, and construct an understanding around this idea together.

Back to my notebook: I honed in on directionality. How can I use our time in the handwriting workshops to build the habit and muscle memory of starting letters at the “top” and pulling the writing tool toward the body? I started playing around with images I could draw repeatedly using a line and a curve. I remembered an introductory exercise in a Handwriting Without Tears workbook I used in past years where children are asked to draw a field of grass in order to get their pencil moving in short, controlled lines from top to bottom. I played around with grass, and lines of rain in a big rainstorm. The curve didn’t lend itself as easily to simple images. I drew “sideways rainbows” and colorful “targets” that started with a big C that continued around to make a circle, then changed colors to create another, and another, until my “target” had many layers.

I wanted to help the children build fine-motor muscle memory so they would begin their curve-shapes at the top. “Sideways rainbows” offered a context to play with many different colors and I could envision children enjoying the sensory experience of making curves with different art media, including thick paint, watercolors, and oil pastels.

The c-shaped curve is the first stroke in the first three letters of my 4-year old son Oscar’s name. He warmed up by making some sideways rainbows, then created this same curve shape as he started his O, S, and C. When he moves on to lowercase letters, the c-shape will help him get his lowercase a going in the right direction, too.

The c-shaped curve is the first move in creating an o. This “rainbow target” activity would help children get their o’s going in a counterclockwise direction, which will also support the correct formation of Q, q, g, and d.

One less-efficient habit I wanted to address through this teaching experiment was the tendency to lift the writing tool mid-stroke or mid-letter. These are the “sticky” uppercase letters; they all start at the top (with a line or a curve) and we imagine the tip of our writing tool is moving through a puddle of honey, stuck to the page until the letter is fully formed.

This series of notebook explorations informed the first day’s activities in the 2-week “teaching experiment.” There were 6 children–4 kindergarteners and 2 first graders. Rain, sideways rainbows, and grass became the “warm-up” activity for the first day of class and for subsequent workshops. I would draw some rain clouds and then ask the children to use sidewalk chalk to create a rainstorm, emphasizing that each raindrop “line” must start up high and drop toward the ground. Later, I would share that the sun came out and shined upon the rain, and we practiced making “sideways rainbows”–concentric curves–starting at the top. Later, we drew mice and hid them with grass, lots and lots of repeated lines, starting at the top, going down into the ground. Part of the mini-lesson before this activity was a conversation about muscle memory. We thought about how a baby’s first steps take hard work, focus, and can be clumsy; but over time, after lots of repetition, our body “just knows” how to take steps and we rarely fall down. As we drew these mini-murals on the sidewalks and courts around campus, we did so with awareness that we were “training our muscles,” thinking carefully about starting each line and curve “at the top'' of the shape, so eventually we would just automatically do it that way. This 2-minute video gives a quick peek of how I integrated some of these “big ideas” around handwriting into the handwriting explorations.

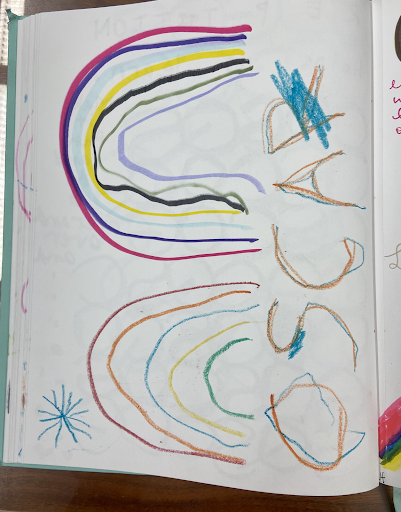

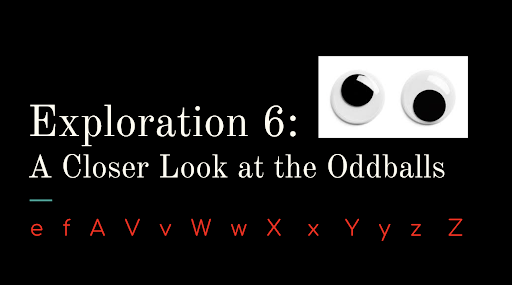

I went on to develop a sequence of 6 explorations over the course of my time with this group of students that allowed me to break up the 52 uppercase and lowercase letters into groups based on a characteristic that they have in common. During our two weeks together, I was able to test out the mini-lessons I had created collecting immediate feedback from the six children who participated in the experiment along the way. The images below share the “big ideas” of each exploration, and some of the scaffolds I discovered and added in immediately to help the children move successfully through the explorations.

Motivation and interest was high during our time together; not only did the 6 children jump into the activities I created, many classmates asked if they could join the activities. We worked mostly outside, using sidewalk chalk, but also were able to repeat and review activities by utilizing paintbrush markers and oil pastels. Overall, the experience was a success because growth in the students’ handwriting was observed over time and everyone found joy and satisfaction in the process.

Impacts on Teaching Practice Moving Forward

As I move forward in my teaching practice, I know that I will use these explorations as the foundation for future handwriting instruction. Inspired by the experience with this small group of students and in response to my observations during the teaching experiment, I have already added scaffolding and additional mini-lessons to the curriculum I developed. For example, one particular “aha” I had early in the experiment was around the need to be explicit about the directional nature of letters, in contrast to non-letter objects, which are less-dependent on their orientation in space. Through some silly conversations about a bottle of glue–how no matter how you turn it or flip it, it remains a bottle of glue–in contrast to letters, which have to stay in a very specific position to remain themselves (otherwise a p is no longer a p, it becomes a b, d, and sometimes even a q). Another learning moment came during the 4th day of exploration, when it became clear that the children needed more scaffolding than I had planned for; I was able to find a way to help them be more successful with the activity in the moment, and I will carry that modification forward the next time I guide children through similar activities.

I also know that I will continue to utilize a variety of art materials to teach handwriting, making the repetition inherent in handwriting practice interesting, sensory in nature, and accessible to those learners whose fine motor muscles are still developing. I will slow down the transition to pencil-paper activities for children who are earlier in their development, keeping letter formation work creative, interesting, playful, and exploratory in nature. I have also begun to develop some pencil-paper activities that can eventually be introduced once children have a strong grounding in the “big ideas” behind the handwriting explorations.

Finally, I can share a simple graphic I developed (like the one below) to name the core habits that will put children who are beginning to write letters on the right track for forming letters efficiently and with correct orientation. It also gives families simple language to guide their children toward these habits at home. Because my students will be familiar with this language from our work together at school, the guiding questions will provide consistency between home and school.

Closing Thoughts About the Critical Role Teacher Scholars Can Play in K-12 Schools

As I reflect on my time as a Teacher Scholar at Hanahau‘oli School, I recognize the critical role Teacher Scholars can play in K-12 schools. The Teacher Scholar role is a unique opportunity to temporarily step back from the daily demands of being a classroom teacher, yet remain connected to teaching. When it is set up as a longer-term role (like it was in my case), it can become a much needed “working sabbatical” of sorts, which can allow teachers to dig into their identified areas of desired growth and professional development. If the time and resources are not available for a full-time Teacher Scholar role, the spirit of the Teacher Scholar could also serve as the foundation for a dynamic and practical approach to professional development at all K-12 schools. Administrators can set aside faculty meetings and professional development days for all teachers to create and explore, individually or in collaboration with others, their own lines of inquiry inspired by their own teaching practice; those who have experience as Teacher Scholars could serve as facilitators within this on-going teacher inquiry process, allowing for a whole new level of agency, innovation, and relevance within a highly personalized style of professional development.

When more and more schools adopt and give resources to Teacher Scholar positions, this will help to inspire and cultivate a growing culture of inquiry among faculty and staff. It will signal to educators on campus that careful observation of practice, questions, experimentation, data collection, analysis of data, and reflection are fundamental parts of the profession. It will become an incredible chance for schools to leverage the individual strengths and areas of expertise of a teacher for the benefit of the entire school community. Through sharing of the Teacher Scholar experience, colleagues will learn from both the products and the process that the Teacher Scholar produces and goes through.

As the progressive education movement grows, and more schools shift to an inquiry approach to learning for students, it is essential that teachers have authentic, firsthand experiences with the challenges and discoveries of the inquiry process themselves. This is essential if teachers are going to effectively facilitate this process with their students. This is learning by doing!

When teachers are supported with the time and space to think critically about their own practice, as I was in the Teacher Scholar role at Hanahau‘oli School, they are empowered to seek, create, and experiment with solutions for the teaching challenges they face, strengthening their teaching practice in order to better meet the needs of the children in their classrooms. The impact of Teacher Scholar work extends beyond the individual teacher and classroom and has the potential to transform K-12 schools in revolutionary ways by giving teachers agency over their own learning and extending the reach of their work to other constituencies at the school, including parents and other teachers, as well as the wider community. At Hanahau‘oli School, the Teacher Scholar role is part of Head of School Lia Woo’s vision of creating a living laboratory, a school where students and teachers alike are engaged in the joyful work of lifelong learning (Woo, 2021). Having experienced a semester as a Teacher Scholar at Hanahau‘oli School, I hope others might be inspired to follow suit, transforming the learning and teaching culture at K-12 schools in profound ways.

Works Cited:

Children, Young People and Families Occupational Therapy Team. (unknown). Handwriting Development. South Warwickshire Foundation Trust. Retrieved at: https://www.swft.nhs.uk/application/files/5614/5995/2571/handwriting_development.pdf

Hellion, S. (2019). Where is the pen? Nurturing handwriting through play. https://helliontoys.co.uk/blogs/news/where-is-the-pen-nurturing-handwriting-through-play

Olsen, J. (2008). Handwriting without tears first grade printing teacher’s guide. Gaithersburg, MD: Handwriting Without Tears.

Woo, L. (2021). Vision for Hanahau‘oli School.

Wood, C. (2017). Yardsticks: child and adolescent development ages 4-14, 4th edition. Turner Falls, MA: Center for Responsive Schools, Inc.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Kristin Baker is a teacher, parent, scientist, literacy scholar, writer, activist, artist, athlete, and language-learner. She has spent the bulk of her 19 year teaching career working with lower elementary students at two independent, progressive elementary schools, one on each coast of the continental United States. Kristin holds a Bachelor of Science in Molecular and Cell Biology from U.C. Berkeley and a Masters of Education in Literacy from Loyola University Maryland. She is currently working as a Teacher Scholar on the faculty at Hanahau‘oli School in Honolulu, Hawai‘i.