By Amber Strong Makaiau and Lia Woo

An often underemphasized and misunderstood essential element of the progressive education movement is its relationship with scientific research. The idea that teaching, learning, and schooling must be systematically studied through observation and experiment has been a defining feature of progressive education philosophy and pedagogy from the very beginning. “As much as they wore their hearts on their sleeves,” early progressive educators like Francis W. Parker, John Dewey, and Ella Flagg Young “prided themselves on their allegiance to science, culling ideas from research from all over the world and exhaustively testing their hypothesis and methods” (Little & Ellison, 2015, p.41).

This overall adherence to the scientific method, carried onto the next generation of progressive education leaders. One of them was Lucy Sprauge Mitchell who explained the following about progressive philosophy and pedagogy:

Our aim is to turn out teachers whose attitude toward their work and toward life is scientific. To us, this means an attitude of eager, alert observation; a constant questioning of old procedure in the light of new observations; a use of the world, as well as of books, as source material; an experimental open-mindedness, and an effort to keep as reliable records as the situation permits, in order to base the future upon accurate knowledge of what has been done. IF we can produce teachers with an experimental, critical, and ardent approach to their work, we are ready to leave the future of education to them (Mitchell, 1931, p. 251).

This fundamental belief that the efficacy of teaching, learning and schooling should be constantly examined and evaluated through the lens of scientific inquiry is at the crux of the ongoing relationship between progressive education and scientific research.

One of the most profound manifestations of the scientific core of the progressive education movement is the Eight-Year Study (also known as the Thirty-School Study). An experiment conducted between 1930 to 1942 by the Progressive Education Association (PEA), this ambitious research project aimed to compare the learning outcomes of students at progressive secondary schools with their peers in more traditional school settings.

The heart of the study was a test of the college success of 1,475 students from 30 progressive schools [who were] matched with an equal number of graduates from traditional schools…who lived in the same kind of community, had the same intelligence rating, the same type of family background, the same general interests and ambitions (The High School Journal, 1942, p. 305).

The educational researchers who carried out the study recorded all of the participants college grades, tracked their extracurricular activities, kept records of interests pursued during personal time, conducted interviews and administered frequent tests to the participants to measure their “ability to think, to work, to get along with other people, to perform their duties as citizens, in general to solve problems in modern living” (The High School Journal, 1942, p. 305).

The outcomes of this extensive scientific study were remarkable.

The students from the experimental [progressive] schools did only slightly better on standardized test scores, but they showed major improvement in other areas, including thinking skills; work habits and study skills; appreciation of music, art, literature, and other aesthetic experiences; improved social attitudes and social sensitivity; personal-social adjustment; philosophy of life; and physical fitness. Students from the most progressive schools showed the most improvement, more than those in the somewhat progressive schools, and much more than those in traditional schools. There was evidence of long-term impact as well (Bruce & Eryaman, 2015, p.10.)

In addition, a meta-analysis of the data was used to isolate the results of the students who were graduates of the “six most progressive schools” (The High School Journal, 1942, p. 306). “It was found that that these students had a greater margin of superiority over their ‘matchees’ than the students from the 30 schools as a whole.”

Since the Eight Year Study, the scientific study of education has proliferated and the notion that teacher-scientists or teacher-researchers produce the most highly effective educators has become best practice in colleges of education. However, the connection between scientific research and progressive education is rarely highlighted as a hallmark of the movement. In fact, quite the contrary has occurred. As Little and Ellison (2015) explain:

Unfortunately… progressive schools continue to be caricaturized as permissive, ‘loosey-goosey,’ ‘touchy-feely,’ and even ‘crunchy granola,’ to the point that many of the minority of Americans who have heard of Progressive Education consider it passe, at best. Amid our current worries that students above all need more ‘rigor’ and ‘basics,’ the stigma is so strong that even some of the most dedicated progressive educators I know have reached the point of making sly references to the ‘p-word’ while jumping on the bandwagon of rebranding trademark progressive pedagogical methods with bland names such as ‘21st Century Learning’” (pp. 27 - 28).

Alfie Kohn (2015) reiterates the point stating that the “tendency to paint progressive education as a touchy-feely, loosey-goosey, fluffy, fuzzy” approach is even more ironic given the “ lack of data to support the value of standardized tests, homework, conventional discipline (based on rewards or consequences), competition, and other traditional practices” (p. 5).

So what can contemporary progressive educators do to reclaim and re-emphasize the inextricable link between progressive education and scientific research? This is a question that Lia Woo, Head of Hanahau’oli School, is both thinking about and taking action on. With faculty and staff she is working to “re-energize our learning community as a unique ‘living laboratory’ where ‘scientific’ exploration and discovery of ourselves, one another, our place (environment), practices and culture will build a foundation to understand and strengthen the education we offer students in our complex, ever-changing world” (Woo, 2022, p.1). She is also making sure to make the link for parents.

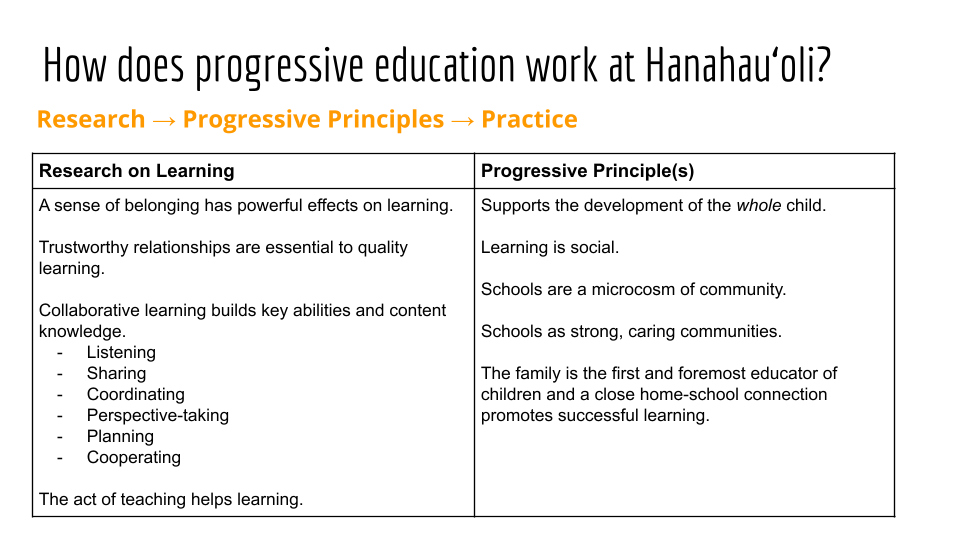

To close out this blog, I share screenshots from the new parent class that Woo currently teaches at Hanahau’oli School. The aims of this class are not only to introduce parents to the inner workings of the school community, but also to ground parents in the progressive education philosophy and pedagogy that guides everyday decision making, teaching, and learning at Hanahau’oli. Core to her message is the critical connection between the school’s progressive education approach and scientific research. She shares:

Fortunately, what may have begun with values (for any of us as individuals, and also for education itself, historically speaking) has turned out to be supported by solid data. A truly impressive collection of research has demonstrated that when students are able to spend more time thinking about ideas than memorizing facts and practicing skills—and when they are invited to help direct their own learning—they are not only more likely to enjoy what they’re doing but to do it better (Kohn, 2015, pp. 5-6).

At the end of the class most parents leave with a deeper understanding of both the historic roots of the movement and our modern day efforts to apply the scientific inquiry process to the ongoing improvement of teaching and learning. They also come to see progressive education as a scientific endeavor. Hopefully, they walk away knowing that a progressive philosophy and pedagogy “isn’t just more appealing; it’s also more productive” (Kohn, 2015, pp. 5-6).

Presentation slides from a new parent class Lia Woo teaches at Hanahau'oli School

Works Cited:

Bruce, C. M., & Eryman, M. Y. (2015). Introduction: The progressive impulse in education. In M. Y. Eryman & B. C. Bruce (Eds.), International handbook of progressive education (pp. 1 - 52). Peter Lang Publishing.

Kohn, A. (2015). Progressive Education: Why It’s Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find.

Little, T. & Ellison, K. (2015). Loving learning: How progressive education can save America’s schools. W. W. Norton & Company.

Mitchell, L. S. (1931). A cooperative school for student teachers. Progressive Education, 8, 251-255.

The High School Journal. (1942). What did the eight year study reveal? (pp. 309 - 305).

Woo, L. (2022). Teachers As Scientists: Watching Life and Children Alertly. Progressive Philosophy & Pedagogy: A Blog For Progressive Educators. https://www.hanahauoli.org/pdc-blogposts/2021/18

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Dr. Amber Strong Makaiau is a Specialist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Director of Curriculum and Research at the Uehiro Academy for Philosophy and Ethics in Education, Director of the Hanahau‘oli School Professional Development Center, and Co-Director of the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy MEd Interdisciplinary Education, Curriculum Studies program. A former Hawai‘i State Department of Education high school social studies teacher, her work in education is focused around promoting a more just and equitable democracy for today’s children. Dr. Makaiau lives in Honolulu where she enjoys spending time in the ocean with her husband and two children.

Lia Woo draws upon her 15+ years of experience in education, specializing in curriculum and educational technology, to lead Hanahau‘oli School. A lifelong learner, Ms. Woo views learning as a source of inspiration and a means to intentional positive change. Ms. Woo’s association with Hanahau‘oli school dates back to 1980 as an entering student in Junior Kindergarten. After graduating from Hanahau‘oli and Punahou School, Ms. Woo received a B.A. in Communications from Boston College in 1998, a M.A. in Learning, Design & Technology from Stanford University in 2002, and a M.Ed. in Private School Leadership from the University of Hawaii in 2016. After curriculum leadership roles at Kamehameha Schools, It’s All About Kids LLC, and Hawaii Pacific University, she returned to Hanahau‘oli in 2012 to teach for four years in Kulāiwi (2nd and 3rd Grades). Thereafter, Ms. Woo served for two years as the School’s first Director of Curriculum & Innovative Technology. Since June 2018, she has served as Head of School. Click here to learn more about Lia’s work at Hanahau‘oli School.