By Sarah DeLuca

The concept of “the 100 languages of children” is one of the most integral aspects of the Reggio Emilia approach. It is based on Loris Malaguzzi’s poem “No Way. The Hundred Is There,” which is a powerful and emotional poem about how children have the right to express themselves in 100 ways. For the full effect, I urge you to pause and read this aloud to your colleagues, partner, friend, or children.

NO WAY. THE HUNDRED IS THERE

The child

is made of one hundred.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.

A hundred always a hundred

ways of listening

of marveling of loving

a hundred joys

for singing and understanding

a hundred worlds

to discover

a hundred worlds

to invent

a hundred worlds

to dream.

The child has

a hundred languages

(and a hundred hundred hundred more)

but they steal ninety-nine.

The school and the culture

separate the head from the body.

They tell the child:

to think without hands

to do without head

to listen and not to speak

to understand without joy

to love and to marvel

only at Easter and Christmas.

They tell the child:

to discover the world already there

and of the hundred

they steal ninety-nine.

They tell the child:

that work and play

reality and fantasy

science and imagination

sky and earth

reason and dream

are things

that do not belong together.

And thus they tell the child

that the hundred is not there.

The child says:

No way. The hundred is there.

– Loris Malaguzzi (translated by Lella Gandini)

The Hundred Languages of Children (1993, p.2-3)

Materials that offer children ways to express themselves in the “100 Languages”

“The 100 languages are a metaphor for the extraordinary potential of children, their knowledge-building and creative processes, the myriad forms with which life is manifested and knowledge constructed” (Reggio Children, 2010, p. 10). In this blog, I focus on the environment, which is considered “the third teacher” because it offers the materials, space, and aesthetic potential for children to express themselves in hundreds, if not thousands, of ways.

Communication and literacy in our schools tends to be heavily focused on speaking, reading, and writing, but what about the language of clay, dance, music, acting out stories, painting, and more? How can providing access for children to express themselves in different languages offer cross-cultural, and cross-language connections? At the Loris Malaguzzi Primary and Preschool, children come from many different countries and cultures, representing the diverse community that surrounds the school. For example, of the twenty children in a five-year-old class I recently observed during my recent study tour, only five of the children were born in Italy, the majority being from Africa, India, and Asia. There, educator Giuseppina Graselli shared: “The ability for children to express themselves in multiple languages (clay, drawing, movement, etc.) allows them to express themselves in more ways, and offers richer ways of communicating and relating to other children.” This is one example of how the physical environment, and the resources and opportunities it offers, can become the third teacher.

Duke and Olivia pound kalo into pa‘i‘ai for a lu‘au

At Hanahauʻoli school we also develop ways in which our environment can become the third teacher. Our school mission states that we value, “critical and creative thinking, and emphasize the important role of the arts as an expression of self and culture” (hanahauoli.org). In addition to time spent in the incredible arts-focused specialist classes of Art, Music, and P.W.L. (Physical world lab), we are constantly asking ourselves in our early childhood spaces how to offer children autonomy and choice in how they wish to express their learning. For example, after learning about how our food moves from farm to table in Hawaiʻi, children might put on a play, create a movie, a large painting, a creation in the sandbox, and participate in the shared community experience of preparing for a lūʻau, to express and celebrate what they’ve learned. While visiting Reggio Emilia my mind and perspective has opened to additional endless possibilities of language and how our Hanahauʻoli School campus and surrounding environments can specifically be set up to offer even more growth opportunities for children to experience.

Cadwell describes the endless potential that the environment plus the materials used in that environment can provide for children:

These materials have the power to engage children’s minds, bodies, and emotions. Their evocative power calls the children into the processes of weaving what they have already experienced in the world with their new perceptions and sensibilities. In this way, the children continue to build and rebuild, through the materials, an ever-expanding awareness and understanding of the world and their place in it…. Each new material gives the child a chance to build another kind of understanding of the richness and complexity of the world. (1997, p. 27)

Over the course of my sabbatical, I have witnessed how our environments can specifically be set up to offer more opportunities for children to engage deeply with them. An incredible example of this is seen in the Atelier spaces of the Reggio Emilia schools I visited.

If it is true that children are immersed from birth in a cultural-symbolic relationship, and learn from the multiple languages of the human experience, the atelier space in the Reggio Emilia schools exemplifies tangible immersive learning for children and adults alike. The atelier space provides opportunities for children to dive into research and creation. Loris Malaguzzi advocated to have an atelier space in each infant-toddler center and preschool with an atelierista, who has an arts background, to work in relation with teachers and children. In the chapter, “From the Beginning of the Atelier to Materials as Languages from Reggio Emilia,” in her book In the Spirit of the Studio, Lella Gandini describes the origin of the Atelier. “Rather than naming the space dedicated to creative exploration with children an "art room," Malaguzzi chose the French term "atelier," which evoked the idea of a laboratory for many types of transformations, constructions, and visual expressions. Therefore the teacher working with children on visual expression was named atelierista, rather than "art teacher” (2015, p. 8).

Atelier spaces in the Reggio Emilia Preschools

A space intended to be even more than a beautiful art studio, “the atelier was most of all a place for research,” (Rinaldi, 1993, p.51) offering specific experiences for children to delve into the 100 languages using all kinds of interesting and intentionally chosen materials. Vea Vecchi, atelierista, describes the power of the atelier:

The atelier serves two functions. First, it is a space that makes it possible for children to encounter interesting and attractive contexts, where they can explore many and diverse materials as well as techniques that have expressive and combinatorial possibilities. Second, it assists the adults in understanding processes of how children learn. It helps teachers understand how children invent autonomous vehicles of expressive freedom, cognitive freedom, and paths to communication. The atelier serves to shake up old-fashioned teaching ideas. (1993, p. 304)

Some examples of the materials in the atelier (and throughout the Reggio Emilia classrooms) are also found in many of our classroom spaces at Hanahauʻoli School, but the extent and amount is what is so different and incredible. Ateliers are meant to be an ever-evolving creative space not limited by a certain set of materials. Examples include:

wooden musical instruments for children to explore and research the relationship to where they came from

clay of many different types and colors, with slips, clay powder, and clay tools

small lamps, projectors, digital microscopes and white walls to illuminate shadows, reflections, and explore properties of light and contrast

Acrylic, tempera, and watercolor paints of multiple shades of a single color, in glass jars that children have mixed themselves

Wire, glass, beads, stones, buttons, bottle caps, shells, and other recycled materials for children to collage

natural materials such as sticks, leaves, flowers, soil, and branches for children to manipulate and explore relationships, reflecting upon their learning

The possibilities are endless.

Ultimately, what results from this space is careful observation and listening from teachers and atelieristas to see what emerges in children’s thinking, hypotheses, and ideas. As researchers, children and teachers are constantly learning, constructing, reflecting, and living in relation with one another. Together they are working in regular concert with our environment, within our society and culture. The use of many languages, tools, and materials to support this research reflects the value of creativity, beauty, and aesthetics. It underscores the importance of creating an environment rich in research potential for children.

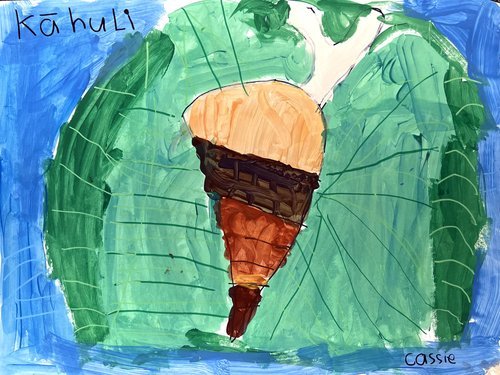

Painting of a kahuli (Hawaiian endemic snail) by Cassie, a Hanahau‘oli student

Vecchi describes how and why the ateliers in Reggio Emilia so intentionally focus on the arts as a means of research and exploration by stating, “we have chosen the visual language not as a separate discipline, devoted to traditional activities; rather, they have focused on the visual language as a means of inquiry and investigation of the world. To build bridges and relationships between different experiences and languages, and to keep cognitive and expressive processes in close relationship with one another.” (1993, p. 310) To me, the atelier helps create a space for children to work on projects, explore, and meld together learning in art and science, all the while finding many ways (the 100 languages) to express themselves. Are there spaces in our classrooms or schools that could serve a similar function?

More than a physical space, pedagogista Carlina Rinaldi challenges us to think deeply about the atelier and suggests “the whole school can become an atelier.” This pushes educators to embrace the concept of a school as a living organism, a place of research. At a recent atelier workshop, an atelierista described the concept of the atelier stating “it’s not a workshop, a specialist class, or an art studio. It’s an area of knowing the world. It’s not necessarily about learning a technique, but a focus on thinking. We encourage children to go deeper, to look for relationships, and put into practice children’s needs to express themselves in different ways . . . an atelier can be outside! It is a mode of being with children.” I personally love and connect to this lens and approach because it invites us as educators, and as people, to take this into our own contexts and create meaningful spaces of research in our own personal and internal ways.

I recently read about one of the most beautiful and moving examples of an atelier in an early childhood center in the book In the Spirit of the Studio. Atelierista Lynn Hall describes a space shared between the preschool and adult day care, and the evolution of an intergenerational atelier. I was moved to tears reading the description of how children and their elderly friends, whom they called Grandmas and Grandpas, worked and played together, creating, gardening, laughing, and developing “strong, respectful, and affectionate relationships.” Hall describes how they learned that the atelier space, “is above all . . . about listening, communicating, and community . . we learned that by slowly and respectfully encouraging relationships and cultivating community, we had discovered the foundation of the idea of our atelier–amiability.” (2015, p. 108)

The atelier, like the Reggio Emilia approach as a whole, is so rooted in this circulation of ideas, hypotheses, creativity, dialogue, respect, and reflection, and allows time and space for children to experience materials while living in relation with each other. This quote by Carlina Rinaldi so beautifully sums up the atelier space:

We are not searching for an "ideal" space, but one that is capable of generating its own change, because an ideal space, an ideal pedagogy, an ideal child or human being do not exist, but only a child, a human being, in relation with their own experiences, times, and culture. . . .The quality of the space can therefore be defined in terms of the quantity, quality, and development of these relationships. Ensuring the existence and flow of this kind of quality is the primary task of relational pedagogy and architecture (1998, p. 115).

Outdoor Atelier experiences

If we think about the atelier as a mindset or way of thinking rather than just a set place or studio, it encourages us to adopt an attitude of research and creativity in our practice as teachers. Children thrive in calming, soothing, challenging, engaging, beautiful spaces with rich learning materials, and are able to bridge connections and develop a more complex understanding of the relationships in our world. As I plan for a new school year, I welcome this newfound opportunity to embrace the environment as the third teacher, to stretch beyond classroom walls and focus on relationships–between people, between materials, between people and materials, and between people and ideas–for a more complete, holistic understanding of the world and our place in it.

Works Cited:

Cadwell, Louise. (1997) Bringing Reggio Emilia Home: An Innovative Approach to Early Childhood Education. New York, N.Y.: Teachers College Press.

Gandini, L. (1993) Connecting Through Caring and Learning Spaces. Gandini, Lella, Edwards, Carolyn P. and Forman, George. The Hundred Languages of Children: the Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp.

Hall, Lynn. (2015) Border Crossing and Lessons Learned: The Evolution of an Intergenerational Atelier. In L. Gandini, L. Hill, L. Cadwell, & C. Schwall (Eds.), In the Spirit of the Studio: Learning from the Atelier of Reggio Emilia. New York, N.Y: Teachers College Press.

Hanahauʻoli School. (2023, June). Mission and Beliefs. Retrieved from: https://www.hanahauoli.org/mission

Indications. (2010, April). Preschools and Infant Toddler Centers of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia, p. 10.

Malaguzzi, L. (2012). No way the hundred is there. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman (Eds.), The Hundred Languages of Children: the Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation (3rd ed.; pp.2-3) Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp.

Rinaldi, C. (1998) The Space of Childhood. Children, Spaces, Relations: Metaproject For an Environment for Young Children. In G. Ceppi, & M. Zini (Eds.) Reggio Emilia, Italy: Reggio Children.

Rinaldi, C. (2005) In Dialogue With Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. London, England: Routledge.

Vecchi, V.. (1993) The Atelier: A Conversation With Vea Vecchi. Gandini, Lella, Edwards, Carolyn P. and Forman, George. The Hundred Languages of Children: the Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp.

Giuseppina Graselli and Debora Rago, The Pleasure of Learning in a Natural Way Presentation, Reggio Emilia Study Tour. Loris Malaguzzi International Center. 2023.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sarah DeLuca is a K-1 early childhood educator at Hanahauʻoli School, where she has been teaching and learning with and from her students, colleagues, and families since 2009. Sarah was born and raised in the Kaimuki area and is an alumnus of Iolani School. She received her bachelor's degree from the University of Oregon in International Studies and her (MEdT) at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She has lived and studied in Italy and enjoys traveling to spend time with extended family there. She finds great joy in working alongside young children, particularly exploring our beautiful island home, creating art, and getting lost in the wonderful world of books.