By Parker Tuttle

The following blog post provides a brief summary of Parker Tuttle's final research project for the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UHM) College of Education (COE) Master of Education in Teaching (MEdT) program. This two-year, field-based program is designed for those pursuing a career in teaching who have earned prior baccalaureate degrees in fields other than education. His project is titled, “Tracing the Loss of Native America: Integrating Geography and Culturally Responsive Teaching into Secondary Social Studies in Hawaiʻi.”

Curiosities Of A First-Time Teacher

Almost two years ago, I found myself observing a freshman English Learner (EL) classroom filled with students whose cultural backgrounds and lived experiences were vastly different from those of their peers. These students, many of whom had not lived in Hawaiʻi for more than a handful of years, were taking a World History course, while acclimating themselves to the content and literacy standards advanced by their new high school. As a pre-service teacher who had only recently been introduced to the term “culturally responsive teaching” (Gay, 2000), I quickly learned that its principles of drawing on students’ cultures, leaning into their prior knowledge and lived experiences, and communicating in culturally and linguistically sensitive ways was directly applicable to my placement. I will never forget my first days of building rapport with students, learning about their lives and where they come from, their past school experiences – both good and bad – and what values and expectations we shared with each other. This first taste of understanding what it means to be culturally responsive – and the classroom experiences and learning curve that followed – suggested to me that pedagogy was integral to success in all classrooms, both here in Hawaiʻi and across the country. Over the course of my teacher journey, my emphasis on nurturing a culturally responsive classroom has only become stronger.

With a declared focus on secondary social studies, all I knew was that I hoped to teach history, at least in part, through the use of a culturally responsive approach and geography. In this ideal setting, students could make sense of the world around them, becoming more spatially aware of the cultures around them as well as celebrating the similarities and differences we share with others. From my own experiences as an impressionable student in my ninth grade World Civilizations class, I could recall how powerful some of our classroom discussions were about historical and current events through the use of maps and various cultural lenses that were different from our own. To capture some of that same energy, I viewed geography as an important discipline and catalyst in which to introduce content to my future students. Around the same time I was introduced to culturally responsive teaching, I began to see parallels between its pedagogical goals of acknowledging students’ cultural knowledge, uplifting narratives consistent with students’ backgrounds and experiences, and raising their combined social consciousness with that of the geography-based classroom I hoped to establish.

Why Culturally Responsive Teaching? Why Geography?

My initial observations turned into wonderings and later into a serious, full-blown inquiry, culminating in a final action research project to satisfy my professional curiosity as well as to empower my fellow teachers in their respective practices. During the initial stages of my proposed research project, I received a better understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy and why educators – especially young student-teachers like myself – should integrate its teachings into their respective practices. By leaning into students’ cultures and experiences (as opposed to unconsciously excluding them), we make learning for them “more relevant to and effective for them,” thereby driving motivation and validating their cultures and identities (Banks, 1997; Gay, 2000). What separates culturally responsive teaching from other “culturally relevant” approaches is its accessibility and flexibility to target students’ academic achievement and critical thinking, where inequities are directly addressed. Having first stemmed from experts like Geneva Gay who were interested in improving the lives of marginalized students of color whose voices and stories had not previously been heard, culturally responsive teaching strives to raise diverse students’ cognitive capacity and cultural competence, addressing important social justice issues like inequity, racism, and bias historically ingrained in our education system (Gay, 2000; Hammond, 2015). While emphasized in teaching preparation programs since the mid-1990s, it is clear that culturally responsive practices are all the more important not only because we live in an increasingly diverse society (both here in Hawaiʻi and nationwide), but also due to alarming contemporary trends in curriculum and resources, which aim to exclude multiple perspectives and diverse voices. Many teaching standards are under attack or have already been rendered obsolete due to recent traction barring states’ curricula and resources advancing diversity, equity and inclusion under the guise of purported “critical race theory” (Schwartz, 2024). Like the rest of the country, teacher demographics in Hawaiʻi (predominantly Caucasian and Japanese) largely remain the same against the backdrop of the ever-growing diversity of its students, suggesting that the value and necessity for culturally responsive teaching in our classrooms has reached its most crucial point.

While geography, often confined to the social studies classroom, does not cover as much ground in terms of how we think about and develop our teaching practices, the discipline, with its use of maps, infographics and other forms of spatial representation, presents unique opportunities to teach students about different cultures, how the world works, and the historical and political events that have influenced change. In many ways, geography has largely fallen out of favor as an explicit subject, especially in the K-12 setting. According to a 2018 study by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) investigating students’ testing performances in geography, there has been no significant improvement since their tracking began in 1994. The study found that only 25 percent of eighth grade students (the same grade level as my own students) reached “proficient” levels (NAEP, 2018). Proponents of K-12 geography education claim this alarming data demonstrates how schools might be jeopardizing students’ basic knowledge of the human, cultural and spatial patterns that geography provides, hindering their ability to see their place in the world and the identities of others from a local and global perspective. When placing this contemporary “myopic” outlook next to the vision of the Hawaiʻi Department of Education whose goal is to set students up for success “in a culturally diverse, technologically complex and interdependent global society,” it becomes clear that geography, as sponsored in the core geography concepts across the K-12 curriculum, is essential in the social studies classroom (Hawaiʻi Department of Education, 2024).

Building a Culturally Responsive and Geography-Based Unit

As a young educator eager to understand how the integration of geography content and culturally responsive teaching can inform and strengthen my own teaching practice, I set out to conduct an “action research” project as part of my student-teaching semester in the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa College of Education Masters in Elementary Teaching program. The possibility of an intersection between the two – and whether or not each complimented one another – became a focal point of the study. What was most critical, however, was the impact that this study would have on my own teaching practice. As a young pre-service teacher, my primary goal was to learn how to connect with my students more effectively, both through the content and the experiences we shared together. I wanted to remind my diverse set of students that their cultural backgrounds and experiences are assets to their own education and can provide a frame of reference as to how they see themselves in the world. The integration of geography and culturally responsive teaching, I believed, could help me achieve this goal.

To guide my formal inquiry into understanding the extent to which geography content can support a culturally responsive classroom, I developed the following research question: In what ways does the integration of geography content and culturally responsive teaching impact students in the secondary social studies classroom? By investigating the impact on my eighth grade students, I looked to gain further insight into their thinking and any other experiences that arose, designing and implementing an entire unit of study to get at the heart of my inquiry. For almost a month, I conducted a unit on Native America and Westward Expansion, examining how the United States acquired new territories and how often their less-than-reputable methods affected both Native Americans and Native Hawaiians, who were similarly exposed to the legacy of U.S. imperialism. By carefully integrating the story of Native Hawaiians in concert with the key events and aftermath of Native Americans, students not only grappled with the commonalities and differences between the two groups, but were also supplied with a responsive curriculum to apply their own cultural knowledge as young children living and growing up in Hawaiʻi.

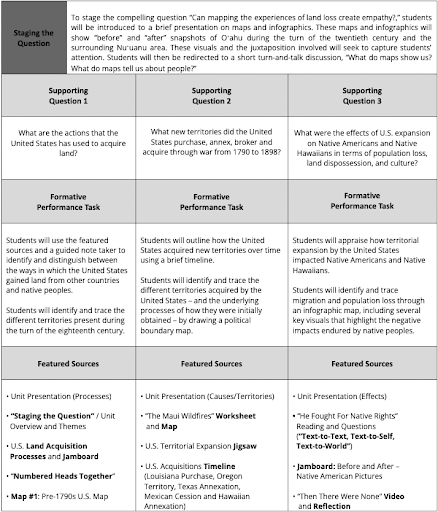

For my student-teaching semester, I taught two standards for our ongoing “Westward Expansion” unit: “Trace how the United States acquired new territories, including purchases, annexation, treaties and war” and “Assess the effects of U.S. expansion on Native Americans in terms of population loss, land dispossession, and culture.” To ground our unit in inquiry (a must in social studies and civic education) as well as address both geography and culturally responsive features of my research question, I developed a unit that invited students to explore the compelling question, “Can mapping the experiences of land loss and identity create empathy?” After much contemplation, I believed this question would facilitate students’ inquiries of the content explored, apply the themes of geography (through geographic tools like maps and infographics) that were natural to the story of indigenous peoples and tribes (e.g. border changes, migration patterns), and promote a culturally responsive classroom rooted in empathy and introspection of themselves and their fellow classmates. I used the Inquiry Design Model, or IDM, as the structure for our “Westward Expansion” unit. The IDM I designed is included below:

Figure 1: IDM Model

To properly explore the compelling question, three supporting questions (see Figure 1), centered around the origins and makeup of land acquisition, and followed by the social and cultural impacts on the native peoples themselves, were introduced to students to provide a clear and sequenced approach to understanding the content. As they grappled with each supporting question, students engaged in a variety of reading and writing strategies designed to promote equity, collaboration, personal reflection, and the sharing of experiences among its participants, each of which represent a particular dimension of a culturally responsive classroom. These exercises included opportunities for students to connect what they just read with their own identities and backgrounds (“Text-to-Text, Text-to-Self, Text-to-World”), engage in alternative narratives and perspectives of native peoples they might not otherwise have been exposed to, contribute in strategically assigned groups that maximize participation (“Numbered Heads Together”), and contribute in small-group and whole-class discussions that target the level of student-centered inquiry the content and compelling question demands.

After each supporting question was answered, students were asked to record, to varying degrees, the places or people they learned about (and the conceptual understanding behind them) onto a map they would hand-draw themselves. With each subsequent map, students would build off their previous mapping. In our classes together, students began with a pre-1790’s America, later transitioning to an 1850’s map that depicted the change in ownership due to land acquisitions. The final map included several infographics, which outlined the migrations of indigenous peoples as well as a personal take about the event from the students themselves (see Figure 2). By introducing these maps, students practiced four of the five themes of geography including location, place, region and movement, participating in activities and discussions that showed where things were, what places looked like, how “place” and entire regions are essential to our identities, and how people were affected and ultimately migrated due to mass social and political changes. By integrating multiple hand-drawn map activities over the unit, students had an opportunity to engage with geography content in a way that was both deliberate and explicit, allowing them to grapple with the cultural and spatial changes faced by Native Americans and Native Hawaiians through a geographic lens.

Figure 2: U.S. Maps and Infographics (1789, 1850s and 1890s Westward Expansion)

My Findings

Since my research question, In what ways does the integration of geography content and culturally responsive teaching impact students in the secondary social studies classroom?, targeted the impact of my curriculum on students, I naturally relied on the words of the students themselves to answer my inquiry. Throughout the unit, students were provided a set of reflection questions to answer following the completion of their maps after each supporting question was answered. The students responded to these reflection questions every week or so. The questions, always the same ones, asked students:

How is doing geography (e.g. maps) helping me learn more about myself, others, and the world?

How is working collaboratively in groups helping me learn more about myself, others, and the world?

Is learning about the experiences of Native Americans making me more empathetic to others? Use examples to support your answer.

How is learning about the experiences of others (e.g. Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, etc.) helping me learn more about myself, others, and the world?

What am I learning about myself, others, and the world in this unit that I haven’t already shared?

At the end of the unit, I compiled all of the students’ responses to these reflective questions and used the “constant comparison” qualitative analysis method to make sense of what they were sharing with me. I detected five primary themes from students’ responses, three of which I share in this blog. The themes include: (1) Visualized change over time; (2) Developed empathy for people far and near; and (3) Connected learning to personal lives and lived experiences.

Through the use of maps and infographics, students were able to visualize change over time, noting in their reflections how their interactions with geographic tools like maps and infographics sharpened their understanding between the past and present through the political changes (e.g. borders, spatial differences) and the larger social dynamics at play. Students described how they gained a stronger handle on identifying “political” changes in maps, or the redrawing of lines and ownership of territory in a historical context, as they progressed over the course of the unit. One student, known here at Student J (names changed to protect the anonymity of my students), noted how they “learned more about how much land was taken and the difference between now and then.” The application of maps allowed the student to juxtapose the “before” and “after” of the political changes, alerting them to the sheer scope, or quantity of land, that changed over time. What was particularly intriguing about this development was how students grew as they moved from map to map, taking these observations of political changes associated with land and its borders, and connecting them to how certain social dynamics and their greater implications played out as the maps changed over time. In his final reflection, one student stated that “It [Geography] shows how places changed over time and how places became more civilized than they were in the past,” suggesting that students were no longer viewing maps as tools that simply showed political changes over time, but also helped them to see the shifts in society that were occuring as a result of these same political changes.

Student K addressed their experience with maps in relation to visualizing the implications for society, this time in relation to the people themselves.

Doing geography with maps is helping me learn more about myself because it has helped me learn more about what some of my Native people’s (Im native Hawaiian) land and territory looked like over the years and what happened to them and how they changed…Its helping me learn more about the world by showing me all the territories of people and leaders of the world and all the changes they have made to it over the years.

In general, these responses indicated that students viewed maps as effective tools to measure changes in society over time, playing a critical role in visualizing the places and people they learned about. They also revealed the progression with students’ previous responses about how they initially made sense of maps showing political changes over time, imparting a more complete picture of how the class visualized change over time.

Students also developed empathy for people far and near, showing signs of understanding and sharing feelings of loss experienced by Native Americans and Native Hawaiians within their respective historical contexts. They also became more introspective in their approach to empathy, applying its underpinnings to their own rationale and real-world experiences. In their responses to the third and fourth questions of their reflections (see above), students reported feeling empathetic toward Native Americans and Native Hawaiians, who were forced to leave their land, adjust to new customs, and adapt to their new surroundings. Student E indicated that they felt “more empathetic… because it makes me think about them having to leave their land from territorial expansion and restarting their lives.”

In general, students used a variety of descriptors – loss of land, homes, necessity, to name a few – as reasons for feeling empathetic toward the plight of indigenous peoples. As students expressed their empathy for the indigenous people, they also began to comment on their own growth. At the outset of our “Westward Expansion” unit, Student L suggested they were only starting to feel empathy toward Native Americans, claiming:

When I heard about Native Americans before, I hadn’t given much thought to them and would think that they had just moved. That was wrong. Now that I learned that there was a lot of war and bloodshed over western expansion (e.g. Nez Percé war, Trail of Tears, etc.), I feel a bit more empathetic towards them.

By the time they reached the end of the unit, however, Student L revealed that their feelings had shifted some, so much so that they felt more empathy for the native peoples in part to the harsh treatment they were exposed to. In their next reflection, Student L wrote:

Before I wouldn’t really care about what happened to people(s) like the Native Hawaiians and Native Americans but now I see that they were forced off their own land, mistreated, and had no say in political matters, I think that it was totally unfair and wrong.

The words of Student L represented just one in a long line of students’ responses that were mature and appropriate to the content they were reading and discussing in class. Many students started to turn inward and reflect on their own experiences and positionality within the larger class of what they learned. In short, students were applying their understanding of empathy to their own rationale and real-world circumstances. For example, Student T conceded they could not possibly understand the position of previous generations of Native Americans and Native Hawaiians, but could only empathize as best they could by learning what happened to them. The student described:

I understand where the Native Americans and also Native Hawaiians come from, I understand the struggles they go to but sometimes I don’t physically or mentally feel the actual struggles they go through but learning about it makes me understand more of the circumstances they went through

In a genuine attempt to make a real-world connection with Native Americans and our society today, another student, Student F, referenced the similarities between the indigenous peoples and economically disadvantaged families today, writing:

sometimes what the people in the past went through is what maybe some kids and people in general might still be going through…even in today’s world. Back then Native Americans had their homes taken away and their land was taken over by white settlers, sometimes if a family can’t afford to pay mortgages or rent for their home they can end up on the streets right away. Sometimes the child could be separated from the family and may need to adapt to their new lifestyle and family.

As perhaps the most glaring example of applying their understanding of empathy, Student F drew on their own frames of reference to highlight the injustices and difficult lifestyle changes they experienced. When placed together, students demonstrated an engagement with the material on a deeper and more relevant level. Through the use of culturally responsive approaches like alternative narratives and the promotion of empathy through group collaboration and the content itself, students displayed clear signs of growth in both their flexibility and application of their learning.

A final theme that emerged was students’ connection to the content with their personal lives and lived experiences. In their reflection questions, students related the circumstances surrounding Native Americans and Native Hawaiians with their own identities. Many students, who identified as Native Hawaiians, drew on their personal connections with the Hawaiian Annexation. These students often utilized words like “ancestors” or “homelands” to describe how they got in touch with the content itself. When responding to the reflection prompt about how the experiences of others is helping them learn, Student G noted the Native Hawaiian story was “teaching me what it was like back then when my ancestors were here, and what they did to fight for their freedom for Queen Liliuokalani to be freed.” Those who made their personal connections clear were reflected in their peers’ discussions as well. In his reflection question addressing collaborating with others, Student H noted how “it [working collaboratively] has shown me… how some people were related to some of the Native people,” suggesting that peers’ stories and experiences were rubbing off on others.

Another group of students also cited the Hawaiian Annexation, though they referenced some of the first generations of Asian-Americans who docked on the islands’ shores. One student alluded to the connection that they and other students had with the many foreigners who arrived as U.S. influence was starting to expand. As Student B describes, “I have learned that we all have a connection to past events. One example is during the Hwaiian [sic] annexation when people from different countries came to work on the land. Many of our families and ancestors came to Hawaiʻi to work.” Student L imparted a similar remark, drawing on how they, as “someone with a Japanese (technically Okinawan) and Chinese background,” saw the Hawaiian Annexation as a source that “helped create my empathy for the first generation of Asian people in Hawaiʻi.”

When placed together, students were empowered by the relevancy ingrained in the “Westward Expansion,” drawing on their personal connections as well as their peers’ experiences to make sense of their learning. Students, without direction, also drew on the central (and culturally responsive) pillar of empathy in increasingly complex ways.

Final Remarks

Based on the results of my study, I found that geography content using maps and infographics can serve as significant visual aids and “connectors” to students’ learning, strengthening their overall historical perspective. The use of culturally responsive teaching – through collaboration, alternative narratives, and equity-based strategies – proved to be mutually beneficial to students’ feelings of relevance to their learning and raised their concept of empathy, affording them the space to connect with their personal lives and lived experiences. Having first assumed this project to learn how to better connect with my students, I can now say that relevancy and inquiry were two critical components that drove my relationship with the class forward. By designing lessons that asked students to collaborate with their peers and discuss issues of indigenous culture or Hawaiʻi they all had a stake in, I noticed a level of depth in discussion and receptiveness that opened new avenues I had not considered before. By integrating geography through visuals like maps, infographics and other related images, students’ inquiries – both current and those posed in the future – were either solidified or subsequently raised, respectively.

Now What?

For an “action researcher” whose project was designed to not only satisfy personal goals, but also offer insights to more learned teachers, I now leave this question to you, fellow educators, academics and subscribers of this blog: What might this study offer educators who might want to integrate geography, culturally responsive teaching, or both in their practices? I realize your answer might differ depending on your respective practice. Some of you may not be a social studies teacher like myself. From where I stand, I believe educators – no matter their area of expertise – should not shy away from engaging in overarching principles like empathy and reflection advanced in a culturally responsive classroom. These are common values that should be taught irrespective of how explicit they are. If we are to make our subject matters come alive for our students, these feelings and skills should be encouraged. At the same time, I encourage you to examine your own biases, so that you redefine your cultural competence and assess the classroom culture you wish to set for you and your students. It is critical to actively reflect and practice the same culturally responsive guidelines you expect from your students, so students know you are open, honest, respectful, and genuinely willing to learn and act on others’ backgrounds and experiences to make learning more meaningful and relevant for them.

For those social studies teachers who are interested in adopting geography into their practice, I would like to emphasize that maps, infographics and accompanying images are your friends. As this study found, these tools support your students’ connection to history and their spatial awareness of the world they live in. Rather than relying on repetition and the frequency that was prevalent (and somewhat required) as part of my “action research” project, I would recommend thinking about your representation of the “who, what, when and where” your maps ultimately convey. It is important to remember that maps and infographics these days do not always contain the borders of a country, the seven continents of the world, or a short blurb denoting a specific culture or feature; rather, they take forms that are increasingly innovative, interactive (think GIFs) and disseminate information that are visually and intellectually striking. Lastly, I would be remiss if I did not point out that geography is and should not be confined solely to the walls of the social studies classroom. There is ample opportunity for other core subjects – Science, English, Math (yes, Math!) – to draw upon the rewarding principles that geography as a discipline provides.

Works Cited:

Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. McGee. (1997). Multicultural education : issues and perspectives (3rd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching : theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Hammond, Z., & Jackson, Y. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain : promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin, a SAGE company.

Hawaiʻi State Department of Education. (2024). Hawaiʻi DOE: Mission. Hawaiʻi DOE | Mission. https://www.hawaiipublicschools.org/ConnectWithUs/Organization/Mission/Pages/home.aspx

The Nation’s Report Card. (2018). Results from the 2018 Civics, Geography, and U.S. History Assessments. NAEP Report Card: Geography Highlights from the 2018 Assessment. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/geography/supporting_files/2018_SS_infographic.pdf

Schwartz, S. (2024, March 20). Map: Where critical race theory is under attack. Education Week.

https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/map-where-critical-race-theory-is-under-attack/2021/06

About the Contributor

Parker Tuttle is a secondary social studies teacher and graduate of the Master of Education in Teaching program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. His academic pursuits are driven by an interest in delving deeper into student-centered inquiries, integrating geography with culturally responsive pedagogy, and fostering civic engagement within the social studies classroom. He previously interned with the Davis Democracy Initiative at Punahou School.